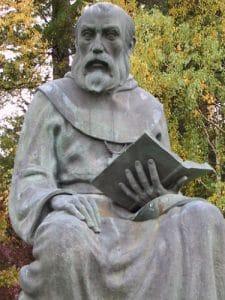

St. Augustine remains one of the most influential authors both in the Christian tradition and in Western culture. His reading of the human condition, of history and of political power remains surprisingly timely. He does not offer instant formulas, but he illuminates the foundations from which we continue to think and believe. His starting point is the interiority of man, that heart that searches and does not rest until it finds its true end.

From this interiority open to the infinite, we can also understand the project of the De Trinitate, where Augustine maintains that in the depths of the human soul is reflected, in an imperfect but real way, the dynamism of memory, understanding and will. Through this analogy, he does not intend to resolve the Trinitarian mystery, but to show that man has been created for communion. Interiority is not enclosure, but openness; the spiritual life does not isolate, but orients toward a relationship with God and with one’s neighbor. This anthropological vision prepares the ground for his conception of history.

It is in The City of God that Augustine unfolds the most profound synthesis between faith and history. There he affirms that two forms of love build two distinct cities: an earthly city, originating in the disordered love of self to the point of contempt for God, and a city of God, born of the love of God to the point of relativizing oneself (The City of God XIV, 28). These two cities are not two geographical spaces or two perfectly delimitable institutions, but two orientations of the human heart. Both cross all peoples, all cultures and all persons; both coexist intermingled in history, making it impossible to draw visible boundaries. Human history is precisely this conflictive intertwining of the search for God and the search for self.

It is in The City of God that Augustine unfolds the most profound synthesis between faith and history. There he affirms that two forms of love build two distinct cities: an earthly city, originating in the disordered love of self to the point of contempt for God, and a city of God, born of the love of God to the point of relativizing oneself (The City of God XIV, 28). These two cities are not two geographical spaces or two perfectly delimitable institutions, but two orientations of the human heart. Both cross all peoples, all cultures and all persons; both coexist intermingled in history, making it impossible to draw visible boundaries. Human history is precisely this conflictive intertwining of the search for God and the search for self.

Augustine describes the city of God as a community on a journey. In a famous passage he affirms that the heavenly city, while on pilgrimage on earth, “calls citizens of all nations and gathers a pilgrim society in all languages, without worrying about what is different in customs, laws and institutions” (The City of God XIX,17). This is one of the most universalistic pages of all ancient Christian thought. The Church, as a historical sign of the city of God, is not defined by ethnic belonging, nor by concrete human institutions, nor by closed cultural traits. It lives in hope, always oriented towards the ultimate future promised by God, and opens its doors to all peoples without exception.

The earthly city, for its part, is not an absolute enemy, but a necessary order within historical life. It guarantees a certain level of justice, ensures coexistence and seeks a possible peace among peoples. However, its peace is always limited and fragile, and can never be identified with the definitive peace of God. This is why Augustine maintains that the earthly city can only offer temporary relief, while the fullness of peace belongs only to the Kingdom of God. This clarity dismantles any attempt to sacralize the state, the empire or any form of political power. Augustine recognizes the value of politics, but also its radical limit.

The earthly city, for its part, is not an absolute enemy, but a necessary order within historical life. It guarantees a certain level of justice, ensures coexistence and seeks a possible peace among peoples. However, its peace is always limited and fragile, and can never be identified with the definitive peace of God. This is why Augustine maintains that the earthly city can only offer temporary relief, while the fullness of peace belongs only to the Kingdom of God. This clarity dismantles any attempt to sacralize the state, the empire or any form of political power. Augustine recognizes the value of politics, but also its radical limit.

From this recognition is born a distinction that has profoundly marked the Christian tradition: the difference between power and authority. Although Augustine does not formulate it in unified technical terms, all his work presupposes that political power belongs to the temporal order and needs to administer the earthly city, while true authority belongs to the spiritual order and orients toward man’s eternal destiny. Power organizes; authority gives meaning. The former establishes laws; the latter recalls the ultimate measure of all human action. This balance allows the Christian to collaborate in public life without absolutizing it, to serve the common good without idolizing any historical structure.

From this recognition is born a distinction that has profoundly marked the Christian tradition: the difference between power and authority. Although Augustine does not formulate it in unified technical terms, all his work presupposes that political power belongs to the temporal order and needs to administer the earthly city, while true authority belongs to the spiritual order and orients toward man’s eternal destiny. Power organizes; authority gives meaning. The former establishes laws; the latter recalls the ultimate measure of all human action. This balance allows the Christian to collaborate in public life without absolutizing it, to serve the common good without idolizing any historical structure.

The Christian life, in this vision, is understood as a journey. Augustine expresses this in a particularly vivid way when he exhorts the faithful not to stop: “Sing as wayfarers sing; sing, but go forward. Soothe your toil with singing; do not love laziness. Sing and walk” (Sermon 256:3). In these words is condensed all his historical spirituality: faith is a song that sustains the effort; the way is the charity that moves; vigilance against laziness is the responsibility before the mission. The Church is, for Augustine, a community of pilgrims that advances with hope, sustained by grace, called to transform history without confusing it with the final goal.

Augustine’s actuality is perceived precisely in this double tension. The city of God orients, relativizes and purifies; the earthly city organizes, sustains and structures. Christian faith does not replace historical action, but frees it from the idolatry of power. Politics does not save, but it is an indispensable sphere for the exercise of charity and justice. Living between the two cities demands discernment, humility and hope. This is why Augustine’s work continues to be a point of reference for the Church: it reminds us that we are citizens of time and eternity, called to serve the world with our feet on the ground and our hearts in God.