In this commentary on Sunday’s Gospel, Fr. Luciano Audisio delves into how Jesus reveals that God is not God of the dead, but of the living, and calls us to live from now on in the logic of love that conquers death.

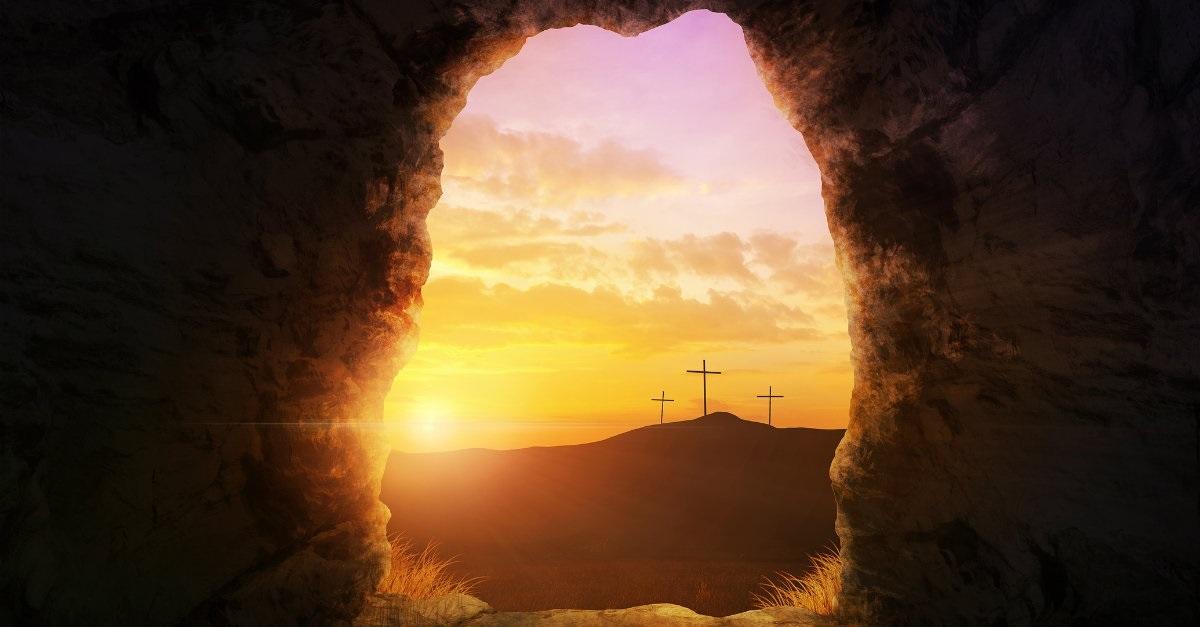

Today’s Gospel places us before one of the most profound and essential points of our faith: the resurrection of the dead. From the origins of Christianity, the Easter proclamation-“Christ is risen”-has not only been the proclamation of an event that occurred centuries ago, but the living certainty that we too, united with him, will rise again. The resurrection is not a distant event, but a reality that crosses and transforms our present existence. St. Luke presents Jesus in Jerusalem, facing the questions of his adversaries. Among them are the Sadducees, a religious elite that denied the resurrection and any form of life beyond death. With irony, they pose to Jesus an absurd situation: a woman who, according to the law of levirate marriage, marries seven brothers in succession. “Whose wife will she be in the resurrection?” they ask, trying to ridicule the hope of eternal life. But Jesus, far from dodging the question, transforms it into a decisive revelation about God and about the human being.

Faith in the resurrection was not present from the beginning of Israel. The people of the covenant first knew God as the liberator of Egypt, the one who saves in history, the one who restores life when all seems lost. In the beginning, salvation was understood in an earthly key: to live many years, to have descendants, to possess the land. But, little by little, Israel discovered that God does not limit himself to prolonging life, but creates life where there is none. The prophet Ezekiel, in chapter 37, expresses it with the vision of the dry bones: “I will open their graves and bring them out of them” (Ez 37:12). That image, which at first represented the return from exile, became in time a real announcement of God’s victory over death. During the persecution of the Maccabees, this hope reached its maturity. Many Israelites preferred to die rather than deny their faith, convinced that “the King of the universe will raise them up to eternal life” (2 Maccabees 7:9). Thus was born the certainty that God does not abandon his faithful even in death; that God’s love and faithfulness are stronger than the grave.

In contrast to this hope, the Sadducees embody a closed vision, incapable of imagining anything beyond the limits of this life. Their story of the woman and the seven brothers – where the number seven, symbol of creation, becomes a sign of destruction and death – is an anti-narrative, a kind of parody of faith. But behind his question lies an existential anguish. There are no neutral questions: every intellectual doubt hides a fear or a desire. Deep down, the Sadducees represent modern man who fears death and, therefore, denies it; who cannot accept the existence of an afterlife because he does not dare to trust in the creative power of God.

Jesus welcomes the challenge of the Sadducees and responds with a much deeper vision of marriage and of life itself. He makes them understand that marriage cannot be reduced to a matter of biological survival or to the mere human need for companionship or belonging. In its truest sense, marriage is a communion of life, a mutual self-giving in which each gives himself or herself entirely to the other. When it is conceived only from practical or social criteria, its deepest meaning is distorted: to be a sign of God’s creative and gratuitous love. Jesus thus raises the discussion to a transcendent perspective. It is not simply a matter of organizing earthly life, but of understanding that we are all called to participate in life in its fullness. For this reason, he refers to the episode of the burning bush, when God reveals himself to Moses as the “God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob” (cf. Ex 3:6). With this reference, Jesus completely transforms the meaning of the dialogue: the God who revealed himself to Moses is not a God of the dead, but of the living. His ardent and inextinguishable presence is a sign of a life that cannot be contained by death.

Like Moses before the bush, we too are called and sent: sent to liberate, to kindle hope where slavery reigns, to restore life where there seems to be only ashes. In this mission is revealed the profound meaning of the resurrection. Life, in its most authentic dynamism, is already a process of resurrection: a constant vocation to pass – and to make others pass – from death to life. This is, in the end, the true meaning of marriage and of every human existence: to live in the logic of gift, in love that does not die. In every sincere self-giving we anticipate the promise of the resurrection, the certainty that, in Christ, we will be led to the fullness of life that has no end.

Today Jesus invites us to look beyond our small securities and fears. He reminds us that God is not a God of the dead, but of the living, and that in him we all live. To believe in the resurrection is to believe that nothing good is lost, that everything we truly love will be transfigured in God. Let us ask the Lord to enliven in us this hope: that we may not fear death, that we may know how to live with our eyes fixed on the life that does not end, and that, while we walk in this world, we may help others to pass – with us – from death to life.