Netflix has done it again. It has launched a series that, under an attractive aesthetic and a tense narrative, puts its finger on one of the issues that most concern parents, educators and public officials: adolescence as a stage of risk. Adolescence is not a documentary, but its fiction is woven with threads of reality as raw as it is close.

Netflix has done it again. It has launched a series that, under an attractive aesthetic and a tense narrative, puts its finger on one of the issues that most concern parents, educators and public officials: adolescence as a stage of risk. Adolescence is not a documentary, but its fiction is woven with threads of reality as raw as it is close.

Each of the four episodes immerses us in a specific hour of the same day. The narrative is articulated in sequence shots, a technical resource that gives each episode a continuous and claustrophobic tension: no cuts, no pauses, no escape. As in life itself.

The protagonists are neither heroes nor villains. It is not only the story of a child, it is the story of a family, of a school, of a community. Each of the characters is the mirror of a generation often misunderstood. And that’s why this series is not for teenagers. It is especially for parents. In this article we start from two fundamental theses, then we analyze three important themes and conclude with a brief reflection.

A fictional story, a very real problem: knife crime in Spain

Although Adolescencia is presented as a work of fiction, what it portrays is an alarming reality that is growing in our streets: the increase in knife crimes among young people. According to the legal-criminological report published by Indret in January 2024 -entitled Crimes with a knife in Spain: a legal and criminological analysis by David García-Aristegui-the number of offenses committed by minors with knives has grown steadily in recent years.

The report notes that in Madrid alone, between 2016 and 2021, knife crimes almost doubled, and highlights a “growing prominence of adolescents” as perpetrators or victims, with increasing presence in areas where poverty, exclusion and lack of parental control converge. In addition, he notes that many of these young people carry knives not with direct homicidal intent, but as a symbol of protection, intimidation or social status (García-Aristegui, 2024, pp. 10-12).

These data coincide eerily with what the series shows: adolescents who, trapped in an environment of peer pressure, social networks and emotional emptiness, resort to violence more out of fear or inertia than out of criminal conviction.

Do we speak the same language as our children?

The second major issue addressed by the series, albeit in a more subtle way, is that of communication, or rather, generational miscommunication. Or rather, generational miscommunication. Do we really know how our children speak? What codes do they use in social networks? What do the emojis they send or the hashtags they follow mean?

In Adolescence, cell phones are just another character: they show, hide, deceive and reveal. They are window and prison. The use of certain terms, emojis or expressions only makes sense within a youth subculture where emotions are disguised as irony, hidden under memes or silenced with stickers. Adults in the series -parents, teachers, policemen- appear out of place, without tools to interpret the signals.

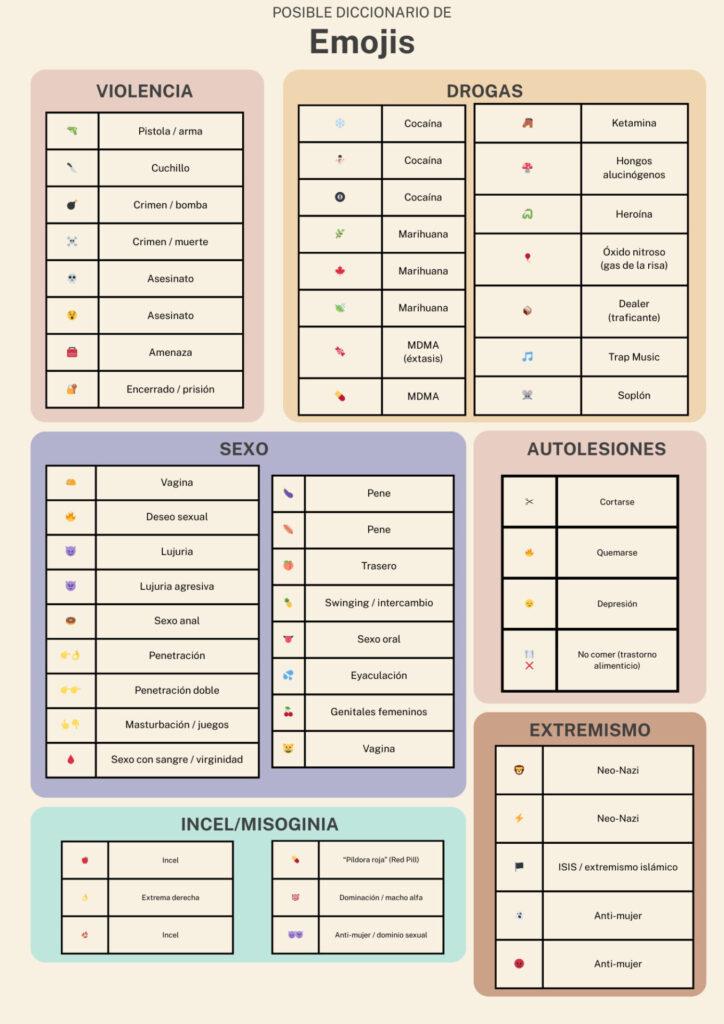

This mismatch is very present in reality. A recent article in the ABC newspaper warned that many parents are unaware that their children may be communicating risky situations (such as drug use or sexual encounters) using seemingly innocent emojis such as (butt), (female sexual organ) or (ejaculation). The key question is: are we able to understand what our children are communicating, even when they do not say it openly?

Three important issues

1. The incels: Jamie and the silent radicalization.

In the third episode of the series, during the evaluation of Jamie by psychologist Briony Ariston, key details are revealed: the teenager actively participated in ‘manosphere‘ forums, digital spaces where hate speech towards women is concentrated. Although Jamie never utters the word ‘incel’, his language and justifications (“she was laughing at me“, “they always prefer the popular guys“) clearly reflect this ideology.

In the third episode of the series, during the evaluation of Jamie by psychologist Briony Ariston, key details are revealed: the teenager actively participated in ‘manosphere‘ forums, digital spaces where hate speech towards women is concentrated. Although Jamie never utters the word ‘incel’, his language and justifications (“she was laughing at me“, “they always prefer the popular guys“) clearly reflect this ideology.

The psychologist asks him if he felt rejected by Katie, and he responds with phrases that evoke resentment rather than pain. The camera – in a fixed, oppressive shot – shows Jamie unable to empathize with the victim. There is no crying, no anger, just a dangerous emotional disconnect.

This kind of thinking does not come out of nowhere. Jamie’s character is precisely constructed: a victim of bullying, without a father figure present, with unfiltered access to the Internet. All this creates an ecosystem conducive to hate speeches that offer him a false sense of belonging.

Incels and radicalization in community: when pain turns into contempt

One of the most disturbing findings in recent studies on adolescence and digital culture is that many radicalization processes do not take place in solitude, but in community. This is the case of incels (short for involuntary celibates), young people -mostly boys- who, frustrated by their lack of success in affective or sexual relationships, find in certain virtual spaces an echo to their suffering… but not a healthy outlet.

On sites like 4chan or certain Reddit subforums, many teenagers find an echo to their emotional frustration, but instead of receiving emotional support, they end up submerged in discourses that naturalize violence, discrimination and contempt for the other sex.

According to the BBC, this movement has gone from fringe to worryingly widespread. Some users are radicalized to the point of justifying rapes, attacks or murders as acts of “revenge” against a society that has “rejected” them.

The BBC Mundo article points out that these communities not only validate the pain, but feed it, transform it into resentment and project it outward: against women, against “chads” (attractive men), against society. What began as a forum for sharing experiences of loneliness quickly becomes a breeding ground for misogyny, hatred and, in extreme cases, violence.

In these digital spaces, teens encounter three very dangerous things:

- Shared identity: feeling part of a group that “understands“themmore than their family or school environment.

- Simplified narratives: ideas such as “they are to blame“, “the system is designed against us“, or “the only solution is to punish“.

- Constant reinforcement: memes, catch phrases, distorted testimonies that validate their vision of the world and anesthetize their critical capacity.

Adolescence, the series, reflects this logic accurately: Jamie is not a monster. He is a lonely boy, without emotional tools, who has found in the internet a community that offers him something that no one else gives him: explanation, belonging and direction. The problem is that those three things are tainted by contempt, anger and affective disconnection.

Incels are a symptom, not a cause. Their existence speaks of a masculinity that has broken down and does not know how to rebuild itself. It speaks of adolescents who feel that they do not fit in, that they are not seen, that they are not wanted. And when no one listens to them, they listen to those who shout the loudest, even if those shouts are full of venom.

As adults, the challenge is not only to detect these signs, but to offer something better: companionship, listening, healthy models of male affectivity, real emotional education. Because if we do not give them language to talk about pain, they will end up screaming from hate.

2. Emojis as a double-edged sword

During the second episode, when the police analyze Jamie’s cell phone, it is mentioned that the conversations with Katie contained encrypted messages. The use of emojis in class chats is explicitly mentioned. Although the adults do not understand the content, the teenagers are clear: emojis are their code.

Specifically, a conversation is shown in which a sequence of symbols appears: -apparently harmless, but which in the context of adolescent language can be translated as a sexual proposal or a sexual teasing. In the statement of a classmate, it is mentioned that “everyone knew what it meant”.

The series shows the generational disconnect starkly: parents and teachers don’t understand what’s going on because they don’t speak the same language as their children. But that language is there for all to see… you just have to learn to read it.

A viral post on Facebook, shared by thousands of users, lists the “hidden dictionary” of these symbols. It is an example of how young people create a parallel – almost hermetic – communication for the adult world. In the image below you can see a translation

3. Privacy and surveillance: when everything can be known

One of the most disturbing elements of Adolescence is its hyper-realistic portrayal of the police process. Jamie is detained after a complete tracking of his location, browsing history, social media activity and cell phone metadata. All without ever setting foot outside the neighborhood.

The opening episode shows how the police review his searches: “how to delete conversations on Signal”, “Red Pill forum“. At another point, his geolocation history is accessed, revealing that he was near the park where Katie was found, although he denies it.

This use of technology to reconstruct a case highlights an uncomfortable message: teenagers think they can hide their digital footsteps, but in reality everything leaves a trace. And at the same time, adults think they’re in control… but they don’t know what they’re looking for.

The series does not fall into technophobia, but it does issue a clear warning: we live in a world where surveillance is constant, and that has legal, ethical and family implications. Parents should teach their children not only to protect their privacy, but also to consciously use their digital freedom.

Conclusion: Our children are not bad, but they live in a wounded society.

Adolescence does not pretend to provide easy answers. It does not point out single culprits or offer magical solutions. But it does force us to take a fresh look at a reality that many prefer to ignore: our children grow up in an environment saturated with stimuli, over-information and influences beyond our control. They live in a wounded society, and often, without our noticing it, this wound becomes contagious.

Many teenagers act like penguins

One of the most revealing moments of the series is when the psychologist asks Jamie, “Why did you do what you did?” and he, after a long silence, replies, “Because everyone would do it.” This sentence, brutal and empty, sums up one of the most uncomfortable truths: many teenagers act like penguins, replicating what they see, what others do, what is expected of them so as not to be left out of the group. In biology, this is called creeping behavior. In real life, it can be lethal.

Adolescence is not a crime. It is a stage. But if we do not accompany it, it can become a sentence. And the good news is that it is never too late to start walking with them.

It has been pointed out many times that the word adolescence comes from the Latin ‘adolescens’ (young boy), which in turn derives from ‘adolescere’, that is, “to grow up”. But this word is also linked to the root ‘doleo’, meaning “pain”. Etymologically, therefore, adolescence links growth with pain: the fact of suffering.

And here is the big question that the series leaves resonating:

What really hurts our teenagers?

Answering this question is not theirs alone as parents, but as a society. But parents have the privilege – and the responsibility – to be the first to ask. Not to watch, but to be. Not to judge, but to welcome.

Alfonso Dávila, OAR.