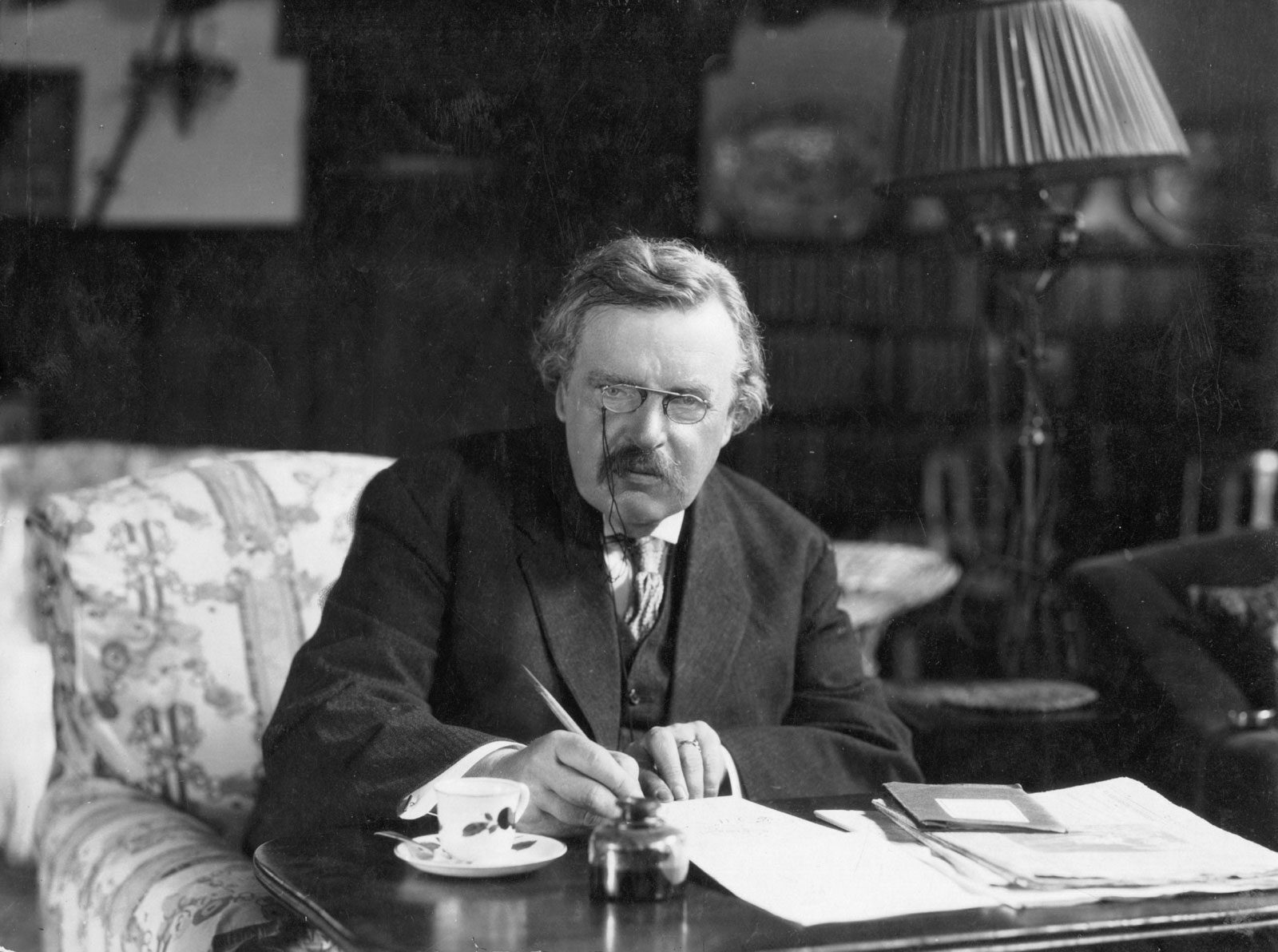

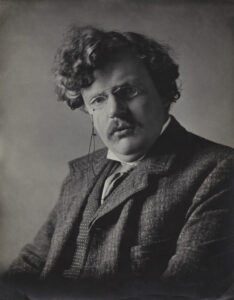

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in England in 1874 in the Anglican Church and died in 1936 after joining the Catholic creed in 1922. He is an intuitive thinker and a genius in the deep sense of the term. He was a writer of novels, prolific essayist, prolific journalist, poet, lecturer, polemicist on a thousand fronts and in many interventions related to politics and social movements that swarmed between the late nineteenth century and the first part of the twentieth century. He confronted naturalism, realism, socialism, and the scientistic world adverse to the approaches of tradition and classical philosophy. An ideological field very similar to that of our days, precisely because today we are harvesting what at the turn of the century were the seeds.

Nowadays, what is being highlighted most about this multifaceted genius is the fact that he converted to Catholicism. Why was he baptized in the Catholic Church? This is the constant question of his friends and also of his adversaries. He answers: “To free me from my sins”. His Anglican co-religionists reproach him for his passage to the Catholic Church, and he, declaring that he had always been searching for the full truth beyond his Protestant line, affirms: “The key fits the lock; I have crossed the threshold and now I believe that I live in the truth”. In the Catholic doctrine he has finally found the coherent truth that responds to his intellectual and theological searches “surrendering” – so he writes – to the weight of truth. Masterpieces such as Herejes and Ortodxia are a display of surprise and paradox, of novel ingenuity and classical reciedumbre, all mixed in random doses to give answers that dismay the listeners of his debates and continue to surprise the reader of our days.

Cardinal John Henry Newman, an Anglican priest who converted to Catholicism in 1845, was canonized in 2019 and in November 2025 Pope Leo XIV conferred on him the title of Doctor of the Church. As if following in the wake of the convert Newman, Chesterton appears a generation later, a thinker who also comes from Anglicanism and who finds in common sense, in tradition and in the joy of healthy humor, the natural way to arrive at the coherent and simple truth, the Catholic truth. And to take the step and be baptized at the age of 48. Surely it is in the series of detective novels featuring Father Brown that Chesterton most clearly shows the empathy inherent in the Catholic faith, empathy in the simple and profound belief that makes the priest detective, Father Brown, an acute agent who solves police enigmas with the magnifying glass of faith and human discernment. His investigative skill consists in the vision of faith with which he penetrates the richness and misery of people. And that kindly empathy comes to Chesterton from the friendship forged with that parish priest, Father John O’Connor, whose common-sense wisdom led Chesterton to his conversion to Catholicism.

Why would it do us good to read Chesterton in our days? The current thrust of the woke agenda, leading to the collapse of reason, was already actively experienced by our author when he polemicized and wrote forcefully against these disruptive ideas. Our writer is very inspiring to face the challenges of postmodernity when he proposes common sense as a guide, when he affirms the Church as the bearer of the healthy and saving tradition, and when he proposes with his sparkling metaphors and paradoxes a sense of humor as an expression of joy and serene conviction in the truth. Postmodern times bring in their banner the culture of emptiness and spectacle, the dissolving nihilism. The Spanish philosopher Iginio Marín affirms: “The woke culture is a mutation of common sense”.

Why would it do us good to read Chesterton in our days? The current thrust of the woke agenda, leading to the collapse of reason, was already actively experienced by our author when he polemicized and wrote forcefully against these disruptive ideas. Our writer is very inspiring to face the challenges of postmodernity when he proposes common sense as a guide, when he affirms the Church as the bearer of the healthy and saving tradition, and when he proposes with his sparkling metaphors and paradoxes a sense of humor as an expression of joy and serene conviction in the truth. Postmodern times bring in their banner the culture of emptiness and spectacle, the dissolving nihilism. The Spanish philosopher Iginio Marín affirms: “The woke culture is a mutation of common sense”.

The Christian faith in the Catholic Church is based on God’s revelation, but it rests on a foundation of common sense, which is a kind of instinct for truth, a practical wisdom, so that faith and common sense go hand in hand. Common sense is not a platitude but a profound intuition. Wit and naturalness make the apologetic works of this thinker -traditional and, at the same time, dissident- evoke childhood, lost innocence, the miracle of everything, astonishment, joy and faith in daily routines, especially in four routines of “homely” wisdom: love, friendship, family and universal citizenship. The prince of paradox, with surprising metaphors, antitheses and twists in argumentative logic, will tell us, for example, that “the only heresy that is not tolerated today is orthodoxy”; that “the most modern is the traditional”, because all forward growth needs a sustaining of the roots, that is, it needs tradition on which to vertebrate the new creations; he says that “the Christian faith represents the greatest adventure a human can undertake”; he affirms that “tradition is the transmission of fire, not the adoration of ashes”; he writes: “Christianity is the only thing that can free us from being children of our time, because it makes us children of God”; affirms that “the cross is always out of fashion because it is true”; proclaims that “orthodoxy is to recover lost innocence”. Common sense, tradition, healthy humor and revaluation of Catholic truth always form the fabric of his ideas.

His pages, besides being full of literary pearls, show that the faith of this man has authenticity of many carats, a thinker who breaks molds and does not allow himself to be entangled by fashionable truths. Today, Chesterton continues to appear as an author who confronts with originality the forest of the twenty-first century’s woke ideologies that he knew in their embryonic origins and unraveled with humor and reasoning already in the first thirty years of the twentieth century. Today it seems that Chesterton returns to the platform of polemics, debates, dialectics or computer media to face the cultural battle. From the praise of common sense and Christian doctrine, Chesterton continues to invite us to believe in the truth and to love it simply. To the “moderns” who accused him of having suppressed the use of reason by throwing himself into the Catholic faith, he replied: “to enter the Church of truth it is not necessary to cut off one’s head, only to take off one’s hat”.

Sense of humor, common sense and sense of faith go together as a natural force in this thinker. That is why today this author is more vindicated than ever. We need him in times when the culture of soft thinking appears as a degeneration of man, as a denial of truth and as a mutation of common sense; we need, I say, a bit of Chesterton, who comes to show us the conviction and joy that emanate from the principles of Christian humanism. To the contemporaries of the end of the nineteenth and the first part of the twentieth century who professed the sciences of naturalism and socialism in the full advance of skeptical scientism, and who cried out that faith was not proper to the educated modern man, our lucid polemicist replied thus: “Take away the supernatural, and you will not find the natural, but the unnatural”.

What does Chesterton bring to us today? A revulsive to live without timidity or emptiness the life of faith in the Catholic Church. He affirms that an eclectic man has a Catholic compass and that sincerity and common sense guide the conscience of people of good faith. He was convinced that if there is no aprioristic predisposition, one will arrive at the truth because whoever dives the paths of life will end up embracing the evident light. A little Chesterton will do us a lot of good, because he gives us fresh ideas for the Catholic message, the agility of living language, a renewed form of communication, an influential force from a friendly and empathetic approach to all, a spirit of new apologetics with charm. In our days of the 21st century, G.K. Chesterton would be a communicator of powerful influence, he would be the most impacting ecclesial “influencer”.